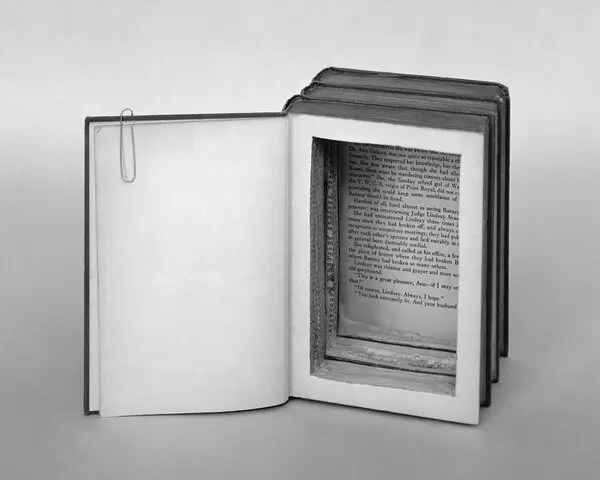

There was a time when novelists held enormous cultural power.

Writers like Philip Roth, Toni Morrison, John Updike, and Alice Walker were once considered the soul of American letters. A new release from one of them wasn’t just a book — it was a cultural event.

Back in the 1980s, when I was in college, new literary fiction would dominate newspapers, spark heated public debate, and influence national discourse.

Fiction was not simply entertainment — it was a mirror to the times, a source of moral reflection, and a tool for collective understanding.

But today?

The bestsellers are dominated by names like Colleen Hoover, fantasy series, thrillers, and romance novels. Literary fiction feels increasingly niche, tucked away in the corners of independent bookstores or academic syllabi.

Is Literary Fiction Truly Disappearing?

According to long-term data from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), the number of people who read literature has been declining since 1982.

And as writer Owen Yingling points out, no work of literary fiction has ranked in the annual top 10 bestsellers since 2001.

This isn’t just about sales figures — it’s about how literature has lost its place at the center of cultural dialogue.

In the 20th century, novelists were seen as prophets, intellectuals, and moral barometers.

Writers like Gore Vidal, Susan Sontag, Truman Capote, and even literary critics such as Alfred Kazin and Lionel Trilling were household names.

Today, the cultural spotlight has shifted — and literary fiction no longer leads the conversation.

The Issue Isn’t Readers — It’s the System

People still love books.

Classic titles like 1984 by George Orwell or Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen sell millions of copies.

So what’s changed? It’s not that people can’t focus — it’s that contemporary authors no longer capture the public imagination the way they once did.

Some of the blame lies with the system that now produces literary fiction.

When Literature Moved to the MFA Classroom

Literature once lived on the streets, in cafes, or in the minds of independent artists.

But since the 1980s, the heart of literary fiction has moved from Greenwich Village to the MFA classroom.

Creative writing programs have professionalized literature.

Young writers now write for each other, rather than for the public.

Literary journals resemble academic publications.

The audience is no longer readers — it’s other MFA graduates.

And while these programs teach “how” to write, they often fail to teach what to write about.

Without grounding in history, politics, science, or art, writers become confined to writing only about themselves — their trauma, their identity, their MFA experience.

The Conformity Trap: The Risk of Self-Censorship

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/cancel-culture-concept-1249723002-0a4be164dd1541be84aa1e8a6680b7ee.jpg)

Fiction once thrived by saying what couldn’t be said elsewhere.

But today, the fear of social ostracism, cancel culture, and ideological purity has led to self-censorship.

Progressive environments, ironically, can create intense pressure to conform.

As a study in the British Journal of Social Psychology (2023) showed, left-leaning individuals tend to hold more rigid and clustered views on social issues, which can stifle diverse expression.

If writers are afraid to offend, they unconsciously write for the narrow elite that polices speech.

And that results in flat villains, safe plots, and generic voices.

Without risk, there is no art.

Writers Must Dare Again

In 1989, Tom Wolfe published a famous essay in Harper’s titled “Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast”.

He called on his fellow writers to step out of their intellectual echo chambers and return to the grand, sweeping novels of Balzac, Dickens, and Steinbeck — works that captured the full drama of a society.

Wolfe himself followed through with The Bonfire of the Vanities, a sprawling novel of New York society.

It still resonates today.

And now, after decades of social and political upheaval, we are once again in need of big, bold fiction that wrestles with the psychological shock of our time.

Literature Is Not Dead — But It Needs Courage

The good news?

The problem with literary fiction isn’t that people don’t care — it’s that writers have stopped taking risks.

Fortunately, many young writers still possess that fire, and there are whispers of a new literary renaissance.

If they can resist the pressures of conformity, they may yet reclaim fiction’s place as a vital lens into the human soul.

No other medium — not TV, not film, not TikTok — can do what the novel can:

enter the interior worlds of others, ask uncomfortable questions, and capture the zeitgeist of a generation.

Even after 600 years, the printed word isn’t going anywhere.

I’m betting on literature’s return — and I believe it will be a powerful blow against the rising tide of dehumanization.

Leave a comment