In recent years, I’ve found myself spending less time on Twitter and more on Substack. That shift has been refreshing. Substack, at its best, is a place where long-form reflection still matters — where nuance has not been completely drowned out by outrage.

This week, while browsing, I stumbled upon an essay by Antonia Bentel. She had asked six people — friends and strangers alike — to define how they knew they were in love.

One woman responded: “I fall in love when someone sees me in ways I never imagined myself.”

A young man said: “Love is seeing myself reflected in someone else’s eyes.”

Another woman explained: “I know I’m in love when I don’t have to pretend to be competent. Love is when someone stays to watch me be messy — my pain, my pettiness, even my unpaid parking tickets.”

And another man compared it to discovering a hidden room in his own home: “Falling in love feels like walking into a room in my house I never knew was there.”

Bentel admitted this was hardly scientific research. Still, she noticed a striking pattern: all of these definitions described love as a moment when another person helps you see yourself more kindly, more fully, more beautifully.

There’s truth in that. All of us long to be seen, affirmed, and cherished. Yet these answers reveal a common cultural mistake: they treat love primarily as being loved, not loving. They focus on what others do for me, not what I give to others.

From Devotion to Narcissism

This is not an isolated quirk of Bentel’s friends. It reflects a much larger cultural drift.

Back in 1966, Philip Rieff wrote in The Triumph of the Therapeutic that traditional moral frameworks were collapsing, replaced by therapeutic values. No longer were we governed by sacred ideals. Instead, psychological well-being and self-comfort became the highest goods.

A decade later, in 1979, Christopher Lasch expanded this critique in The Culture of Narcissism. He argued that the therapeutic ethos had fused with consumer capitalism, producing fragile, self-absorbed individuals desperate for affirmation.

Within such a culture, love inevitably gets misdefined. It becomes less about self-giving devotion and more about receiving attention. Not sacrifice, but reward. Not What can I do for you? but Do you make me feel good about myself?

The Older Definition of Love

This is a profound distortion. In earlier traditions, love was not primarily self-soothing. It was, in fact, self-overcoming.

True love begins with admiration — with being captivated by the beauty, goodness, or dignity of another person. Suddenly, that person dominates your thoughts. You see their face in a crowd. Slowly, your sense of life’s center shifts away from yourself.

The 19th-century French writer Stendhal described this process as “crystallization.” In his 1822 treatise On Love, he wrote that the beloved becomes encrusted with shimmering jewels in the lover’s eyes. Love transforms ordinary traits into something transcendent.

Seen this way, love is not an emotion to hoard but a surrender to someone outside yourself. It is not primarily empowering but disarming. Love is not just a feeling (though it carries many feelings). It is a desire to serve, to be present, to care, to devote yourself.

When two whole selves unite, the boundary between giving and receiving blurs. To give to the beloved becomes indistinguishable from giving to oneself — and, paradoxically, the joy of giving exceeds the joy of receiving.

Erich Fromm and the Art of Love

The psychoanalyst Erich Fromm captured this truth in his 1956 classic The Art of Loving. Love, he argued, is not simply an emotion but an art, a discipline that requires practice.

“To love,” he wrote, “is to have an active concern for the life and the growth of that which we love.”

That means care, responsibility, respect, knowledge, and — most importantly — the overcoming of narcissism.

Love manifests in small acts of service. Bringing a glass of water to your partner at 2 a.m. may not look like poetry, but it is love in its purest form. Even asking for that water can be an act of love, offering your partner a chance to serve, to show devotion.

From Self-Transcendence to Self-Centeredness

Of course, past societies were not always paragons of altruism. But at least their cultural ideals pointed people beyond themselves. Romantic poetry, novels, and songs celebrated the giving of self as the highest expression of love.

By contrast, today’s culture encourages the opposite. We live in the Age of the Self. Humility — once a cardinal virtue, the recognition that I am not greater than others, and others are not lesser than me — has been replaced by a culture of display.

If you doubt that, open Instagram, TikTok, or turn on the nightly news from Washington.

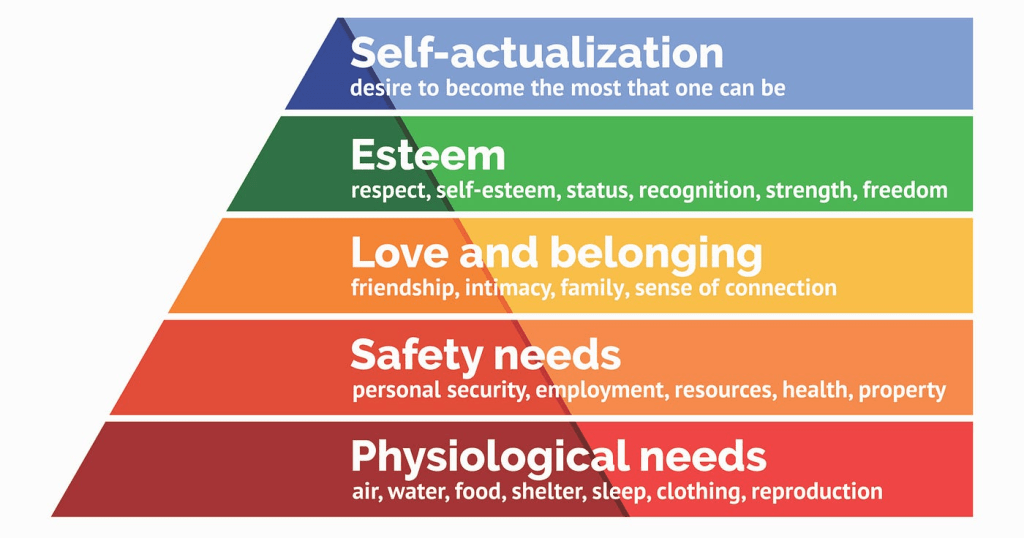

This cultural turn has consequences. Increasingly, we see soaring rates of loneliness, anxiety, and fragile relationships. When society trains people to seek only self-actualization and affirmation, they do not become stronger. They become more insecure, more easily offended, more brittle.

The Narcissist’s Dilemma

Narcissists are notoriously bad at love. Why? Because they cannot see the beloved as an independent reality. For them, others exist only as mirrors.

That is why much of today’s “self-help” literature emphasizes defense, not devotion. Bestsellers like Girl, Wash Your Face, The Subtle Art of Not Giving a Fck*, and, more recently, The Let Them Theory teach people not how to serve others but how to protect their own well-being.

The message is consistent: Don’t let others control you. Don’t sacrifice yourself. Focus only on you.

Of course, boundaries matter. But when self-protection becomes the core definition of wisdom, love withers.

Getting the Order Right

One of the most common phrases I hear today is: “You can’t love others until you love yourself first.”

It sounds reasonable. But it gets the order backward.

The truth is this: you discover yourself as lovable through loving others. It is in the act of giving — of putting someone else’s needs before your own — that you experience your own worth. By seeing your devotion reflected in their flourishing, you learn that you, too, are capable of love and therefore worthy of it.

Love is not primarily about constructing a secure self and then extending it outward. It is about extending yourself outward and, in the process, discovering who you are.

A Culture of Love or a Culture of Narcissism?

Our culture has spent too long nurturing the self at the expense of the other. It has told us that personal branding, self-expression, and self-protection are the ultimate goals. The result has been fragility, alienation, and shallow relationships.

The antidote is not more self-love but more self-giving love. A culture that celebrates devotion, care, and sacrifice will be richer, more humane, and less lonely.

Love, rightly understood, is not a fleeting feeling of affirmation. It is the daily practice of devotion — the art of nurturing another’s life, even in small ways, even when it costs us.

Only then can we recover the deeper truth: we are not meant to find ourselves by looking inward, but by pouring ourselves outward.

Final Thought

To be loved feels wonderful. But to love — truly, selflessly, sacrificially — is the greater joy. It is, paradoxically, the very thing that makes us most lovable in return.

Until we recover this definition, we risk producing not lovers, but narcissists.

Leave a comment