In 1764, about two hundred Irish settlers from Pennsylvania’s frontier marched on Philadelphia.

They were furious at a government they despised — and they already had blood on their hands, having slaughtered a peaceful Indigenous tribe.

They blamed Quakers — who ran the colony — for what they called weak leadership and treasonous leniency toward “savages.”

Many Quakers, long known for pacifism, took up arms in fear of an uprising.

Only Benjamin Franklin’s diplomacy prevented a civil war.

But the peace brought no harmony.

Instead, a pamphlet war exploded, revealing the deep ethnic and religious fractures of the colonies.

Irish Presbyterians were branded “white savages.”

German immigrants were mocked as “Palatine peasants.”

Even Franklin described them as “a swarm of foreigners” who refused to learn English.

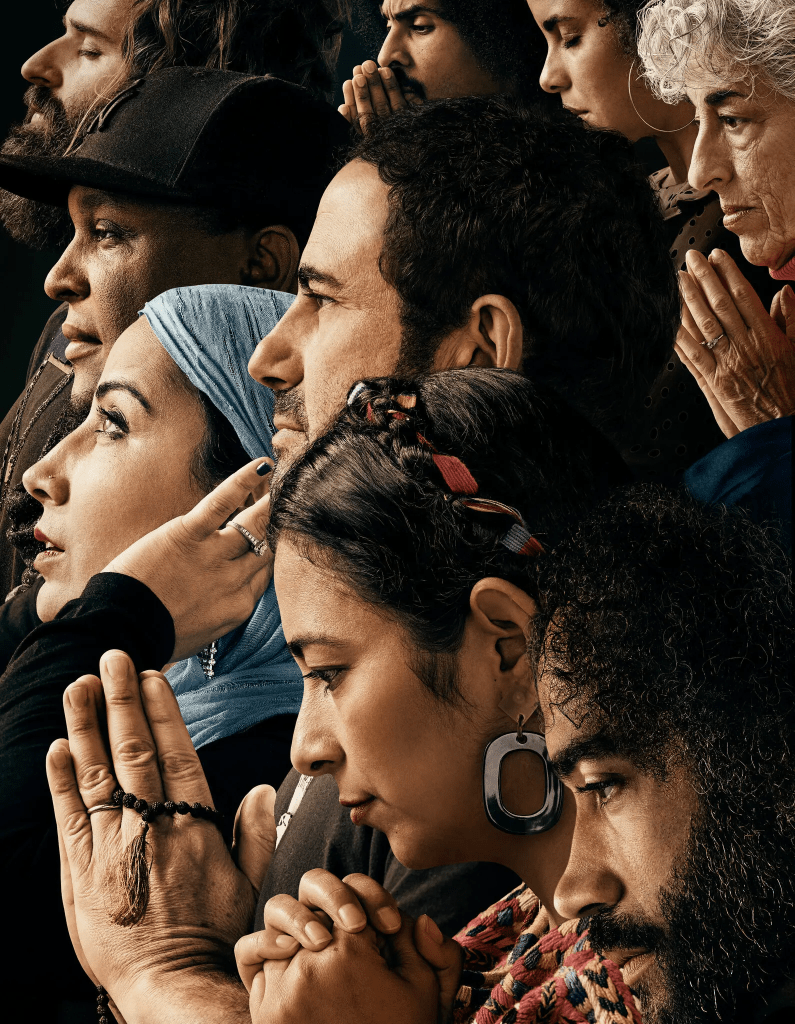

This was colonial America — fractured, suspicious, tribal, and anything but a “united founding stock.”

The modern right-wing fantasy of a pure white Protestant nation is a story invented centuries later.

The Invention of “Heritage America”

Today’s conservative populists insist that “true Americans” are the cultural heirs of the Founders —

that the Founders weren’t merely bound by Enlightenment ideals, but by a shared ethnicity, language, and religion.

Their logic follows: mass immigration has diluted that “purity” and fractured social cohesion.

This sentiment found a home in the Trump administration, which openly tied immigration policy to cultural anxiety.

Recently, The New York Times revealed that the White House discussed prioritizing white asylum applicants over nonwhite ones.

A DHS post titled “Our Nation’s Heritage” romanticized westward expansion and mass deportations.

The far-right website American Renaissance reposted it with a one-word caption: “Approved.”

The word heritage has become a rallying cry on the American right —

a coded shorthand for “White, English-speaking, Protestant, and native-born.”

JD Vance and the Politics of Bloodlines

Vice President JD Vance embodies this idea.

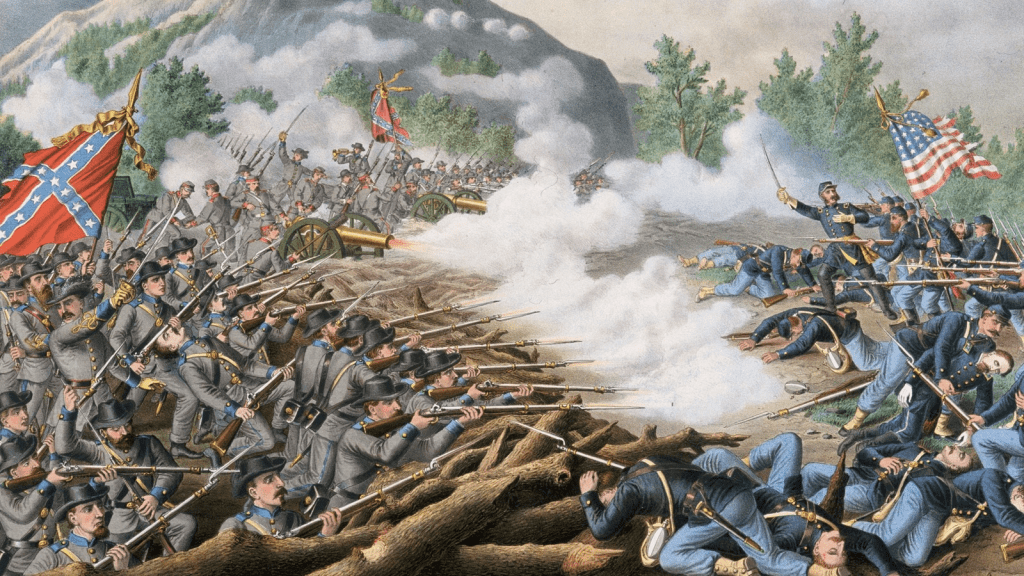

At the Claremont Institute, he declared that “Americans whose ancestors fought in the Civil War have more claim to this nation than those who say they don’t belong.”

At the GOP convention, he went further:

“America is not just an idea. It’s a nation — one people, with a shared past and a shared destiny.”

That message — that blood, not belief, defines belonging —

stands in direct opposition to the pluralistic foundation the Constitution was built upon.

The Historical Reality: Division, Not Unity

The truth is, America was never culturally unified.

Even among the English majority, sects fought bitterly.

Puritans and Quakers were expelled from Virginia; Quakers were hanged in Massachusetts.

New Englanders and Tidewater colonists took opposite sides in the English Civil War.

As historian Peter Silver of Rutgers University writes in Our Savage Neighbors,

the colonies’ exposure to diversity produced not assimilation but defensiveness.

Quakers became more insular; Lutherans insisted on German-speaking clergy;

Irish Presbyterians renewed vows rejecting “the abominations of our times.”

In short, America’s “heritage” was a mosaic of fear and mutual resentment — not harmony.

America’s Real Distinction

Vance’s nostalgia for “pure roots” echoes those colonial anxieties.

He praises his Scots-Irish Appalachian lineage and even celebrates his Indian-American wife —

yet, like many nationalists, refuses to admit that diversity itself is the central fact of American history,

along with all the tension and prejudice that came with it.

America’s greatness was never born from homogeneity.

It arose from building a government that functioned despite division —

from finding unity without uniformity.

The Founders did not erase conflict; they institutionalized it.

If the colonies had been culturally uniform, the Founding would have been forgettable.

The miracle of America is not purity — it’s the refusal to grant any group a monopoly on belonging.

That, Woodhouse writes, “is what being American truly means.”

Leave a comment